Israeli racecar driver Alon Day was the Asian champion in the Formula Renault competition in 2008 and the champion of the European NASCAR series in 2017, 2018 and 2020.

As of January 2022, he has a new job as a virtual driver for Israeli esports company Finest. Day sits at a computer monitor playing sim-racing games while legions of fans watch on YouTube, Twitch and other streaming platforms.

For Day, it’s not such a stretch: As a teenager, he came “to the world of racing through computer games and simulators,” he says. So, “joining Team Finest is a great opportunity.”

Finest is Israel’s first professional esports group. Founded as “Team Finest” in 2019 by Rubik Milkis, with Yotam Nachshon joining a year later, the organization runs teams in four of the most popular multiplayer video games: Fortnite (a Battle Royale game), FIFA (football/soccer), and two first-person shooter games, Counter-Strike and Valorant.

Finest even has a professional women’s team for the latter (impressive given that streaming game viewership is 85 percent male). Finest competes in Israel with Nom, the country’s only other professional esports group.

Esports is big business, with half a billion fans watching their favorite players click, swipe and sometimes stab. Revenues are currently over $1 billion with year-over-year growth at 12%.

Where the younger generation is at

In esports, viewers don’t pay to watch, so where does the money come from?

Some is shared by Finest’s streaming partners. Most, however, comes from sponsorships – just like in nonvirtual sports. Sponsorships pay for prize money, which can reach multiple millions of dollars in some cases.

Among Finest’s sponsors are Pizza Hut, Logitech and Tazos, a leader in the blockchain space that is helping Finest make money in another way – by selling NFTs (non-fungible tokens). You can also buy tangible t-shirts and hoodies on the company’s website.

“Every brand wants to be affiliated with gaming,” explains Tal Perry, chief revenue officer for Radarzero, which owns a majority stake in Finest.

“This is where the younger generation is at and it’s hard to reach them. They’re not listening much to the radio or watching TV. If they’re online, they’re on streaming sites. For traditional content sites, more than a third have AdBlock installed, so they’re not even seeing the advertisements,” Perry says.

“For brands that want to reach this audience, esports is one of the best ways to do it. They can sponsor tournaments or work with gaming influencers who stream content online.”

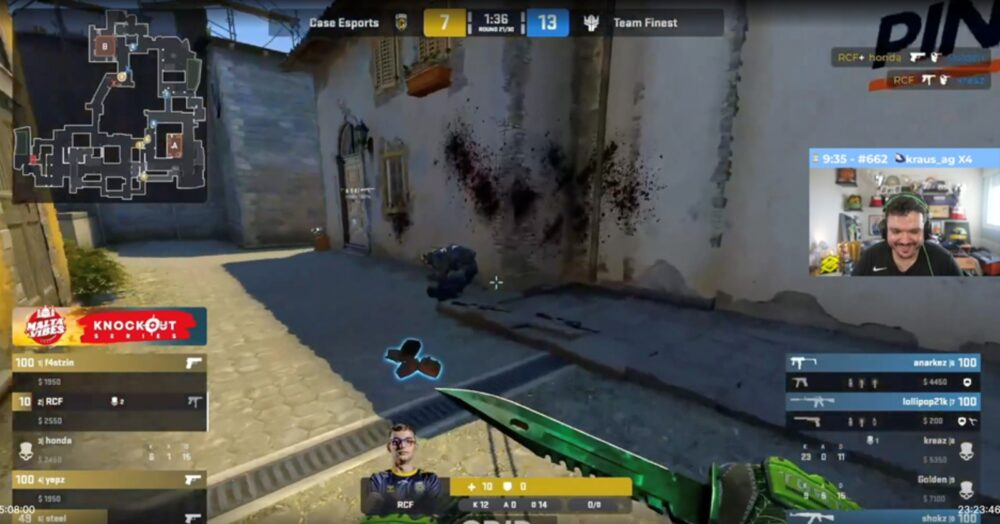

Here’s an example of an online influencer promoting Finest against Case Esports playing Counter-Strike and watching on Twitch.

The video has already racked up over a million views. Indeed, it’s not unusual for a top team in Europe or Latin America to have 45,000 or more concurrent viewers watching live – equivalent to filling up a large stadium IRL (in real life).

In North America, those numbers can climb into the hundreds of thousands of concurrent views. The games themselves are played on the servers of the game makers; Twitch and YouTube only allow fans to observe.

Serious training

Just as with the real thing, Finest players practice six to eight hours a day with a coach. Actual game play might include three or more matches in a day with players on their computers up to 10 hours straight.

Players watch film of the teams they’re due to play against, as well as recaps of their own play so they can talk strategy. Team Finest has a sports psychologist on the payroll. And most important, players get a full-time salary to Twitch and ’tube.

Before the advent of Covid-19, Finest even sponsored in-person bootcamps.

Most esports games are for PCs and consoles rather than the app-based games you play on your phone.

“Not a lot of companies are dealing with this in Israel because the investments are quite high and the length of time until you see revenue is longer than for an app you upload to the app store,” Perry explains.

Perry first met Finest when it was mostly an amateur club not paying salaries or even organized as a legal entity. Today, the company’s teams compete across Europe.

“The teams play in regions, so we don’t play in Asia,” Perry notes. “We’d like to get there,” especially since an estimated 35% of the esports market is in China. “We played against a Chinese team once when they were in a bootcamp in Europe.”

The main problem with crossing too many time zones is latency – that’s when the servers have trouble communicating and the game play stutters and stops.

Pandemic effects

Covid-19 proved to be a surprising boon for Finest. With people stuck at home, “esports grew parabolically,” Perry says. When real-world stadiums shut down, even the TV sports channels started broadcasting esports.

There were downsides, too.

“We had plans for local community tournaments where at least the semifinal would be offline with a live audience,” Perry says. “That had to be scrapped. Sending the team to a bootcamp in Europe had to be scrapped a couple of times, too. Even the prize money for the winners became less, as there were fewer major events.”

But overall, the pandemic “strengthened esports with an audience and generation that weren’t there but were in front of the computer all the time anyway.”

Finest now has over 40 people on the payroll, including all the players, and is building its own “performance room” in Tel Aviv so everyone, as well as those based in Europe, can be together for practices and official competitions.

Not fantasy sports

In contrast to fantasy sports, where gamers draft a team from real-world players and watch them compete, esports has players dedicated to their simulated craft.

Esports got started in the 1970s. The earliest known video game competition took place at Stanford University in 1972 for the game Spacewar. Video console maker Sega began sponsoring arcade tournaments in Japan in 1974. Atari jumped in by 1980 with a video game competition for the then uber-popular Space Invaders. In America, the televised esports program Starcade aired 133 episodes from 1982 to 1984.

Nintendo threw its hat into the esports ring by the 1990s. PC games benefited from Internet connectivity during this period, too, which is when games like Counter-Strike emerged. Nintendo hosted the Wii Games Summer 2010 and, today, even the Olympics are exploring esports options.

To check out Finest, click here

Brian has been a journalist and high-tech entrepreneur for over 25 years. He combines this expertise for ISRAEL21c as he writes about hot new local startups, pharmaceutical advances, scientific discoveries, culture, the arts and daily life in Israel. He loves hiking the country with his family (and blogging about it). Originally from California, he lives in Jerusalem with his wife and three children.

First published on:Israel21c

The copyright belongs to Israel21c and the author.