Iddo Wald shows me two abstract shapes, one angular and the other rounded.

“One of these shapes is called Bouba and the other is Kiki. Which is which?”

“That’s Bouba,” I declare, pointing to the rounded shape.

“That’s what 90 percent of people say,” Wald tells me with a smile.

“It has nothing to do with culture or language. It’s related to how we move our mouths to pronounce those sounds,” he says.

“The sharp sound of ‘Kiki’ and the way our mouths move to pronounce it is associated with the sharp angles of the shape you see.”

The “Bouba/Kiki Effect” was first reported by psychologist Wolfgang Köhler in 1929. The Baruch Ivcher Institute for Brain, Cognition & Technology at Reichman University (formerly IDC) in Herzliya is taking that basic sensory research to places ol’ Wolfie couldn’t have imagined.

The BCT lab’s founding director, Prof. Amir Amedi, is a computational neuroscientist, a pioneer in multisensory research and a world expert on neuroplasticity, brain imaging and brain rehab.

Amedi’s list of accomplishments and awards is long. Very long. Suffice it to say he was named in 2015 as a Genius 100 Visionary along with several Nobel laureates. Fun fact: He’s also a tenor saxophonist with a group called the Jazz Banditos.

Last summer, Amedi graciously invited me to tour the lab. But scheduling a face-to-face with this busy man is like trying to catch a cloud, so we spoke by phone instead.

Wald, BCT’s amiable chief design and technology officer, showed me around the lab in December. And I realized quickly that Kiki and Bouba were the only ones with an IQ close to mine. The humans here are operating at genius level.

Neuroscientists traditionally studied each sense separately, Wald explains. Amedi was among the first to understand that all meaningful experiences are multisensory.

“There are a lot of connections between the senses. In our lab, we look at those connections and how we can create portals between the senses and even reprogram our senses.”

Seeing with the ears

Last July, I reported how a 50-year-old man, blind from birth, learned to recognize objects using Amedi’s EyeMusic invention.

EyeMusic converts visual images into “soundscapes” that activate dormant neural circuits in a blind person’s vision-processing occipital cortex. This “sensory substitution” concept is one of Amedi’s specialties.

“With a lot of practice listening to pictures you can train people to see through their ears,” explains Wald.

“A blind person with no previous concept of colors can actually reach a stage where they can pick a green apple from a bowl of red apples. It means the part of the brain used for sight needs to be redefined, and it also shows that our assumptions about brain plasticity after a certain age were incorrect.”

Amedi discovered that the brain is much more malleable than previously believed.

“What you learn later in life is not less important that what you learn early in life. You can teach the brain at any age even if you are missing input from when you were a kid. If you were never exposed to visual stimuli, it can emerge even at age 50 or 60,” Amedi tells me.

“All the technologies here are inspired by this discovery.”

Speech to touch

EyeMusic training is intense and long, but the lab also is developing sensory substitution techniques requiring little training.

Amedi and postdoctoral research fellow Katarzyna Cieśla pioneered a sensory substitution device that doubles speech comprehension by delivering speech simultaneously through audition and as vibrations on fingertips.

This has obvious benefit for people with hearing impairment. But everyone needs help understanding speech, especially now that facemasks prevent us from seeing the speaker’s mouth.

“All the senses are processed simultaneously. If there is a conflict between vision and audition, you will hear what you see and not what you really hear,” Amedi says.

People with normal hearing lose about 10 decibels – or half of speech content — if there’s a lot of background noise or they can’t see the speaker’s lips. After an hour of training with the speech-to-touch device, 16 out of 17 test subjects gained 10 decibels and understood speech twice as well.

Future wearable implementations of this speech-to-touch device could be useful in situations such as talking on the phone or learning a foreign language.

For people on the autism spectrum who have difficulty comprehending emotions from speech, the lab is experimenting with voice recognition to analyze emotions in a speaker’s voice and communicate them via touch and other sensory input.

Postdoc lab member Adi Snir, who has a PhD in music composition and technology from Harvard, helped develop an audio-to-touch system that conveys location through vibration. This technology could, for instance, hasten response time in semi-autonomous cars by alerting the driver to a hazard in a specific location.

Using a European Union grant, the BCT lab is working to translate temperature to sound. Possible applications include a sound that warms people in a chilly room or that cools factory machinery in danger of overheating.

Nice geniuses doing good

Amedi emphasizes that every development at the institute is meant to do good in the world.

“The entrepreneurial spirit here at Reichman University allows us to dream big and do projects on a very large scale,” he says. “We have brilliant students – not just brilliant but also nice — and powerful tools to study the brain. It’s amazing and fun.”

When Amedi came to Reichman from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2019, he recruited Israeli and international researchers from fields such as auditory and visual arts, computer science, brain science and consumer behavior.

“Our methodology is to take what we know and learn about the brain to design new technologies,” says Wald. “That’s why we have an extremely multidisciplinary team.”

Wald first interacted with Amedi’s team when he was working in Milab, Reichman University’s human-computer interaction (HCI) research and prototyping lab.

“When I read the first draft of the paper they wrote, I had literally no idea what they were talking about,” Wald claims modestly. But he’s no slouch in the brains department.

Wald earned a double master’s in innovation design engineering from London’s Royal College of Art and Imperial College. He was part of the Intel Core development team and cofounded a healthcare wearables startup before a five-year stint in Milab.

Mind over MRI

Wald took me to the new Ruth and Meir Rosental Brain Imaging Center, a sophisticated MRI setup where BCT lab members can “do fantastic things.”

Magnetic resonance imaging is a valuable diagnostic tool. But having to lie still in the narrow dark tube often causes anxiety and claustrophobia. In adults, this leads to less-than-perfect MRIs in 10 percent of cases, and in kids it’s 50 percent. Sometimes people refuse to get an MRI or need sedation.

Amedi’s team is working on inexpensive, easy-to-implement multisensory experiences to relax adults and children in this and other high-anxiety treatment settings.

A research grant from Joy Ventures will help them create technologically upgraded versions of mindfulness meditation, body scan meditation and attention training technique (ATT).

In ATT, patients listen to simultaneous sounds from different locations to train them in turning their attention away from compulsive, unpleasant or anxious thoughts. The experience could be enhanced by creating 3D multichannel recordings combining how different people hear the same sounds due to varying ear architecture.

Adding vision to the mix, the lab is developing glasses that have filters and prisms enabling the illusion of seeing outside the MRI tube.

In a future article, we’ll describe the BCT lab’s collaboration with MRI maker Siemens and Dr. Ben Corn of Jerusalem’s Shaare Zedek Medical Center to craft virtual experiences according to patients’ preferences. Overall, they aim to provide an exceptionally healing, hopeful and relaxing atmosphere for patients, staff and families in the hospital’s new Radiotherapy Center.

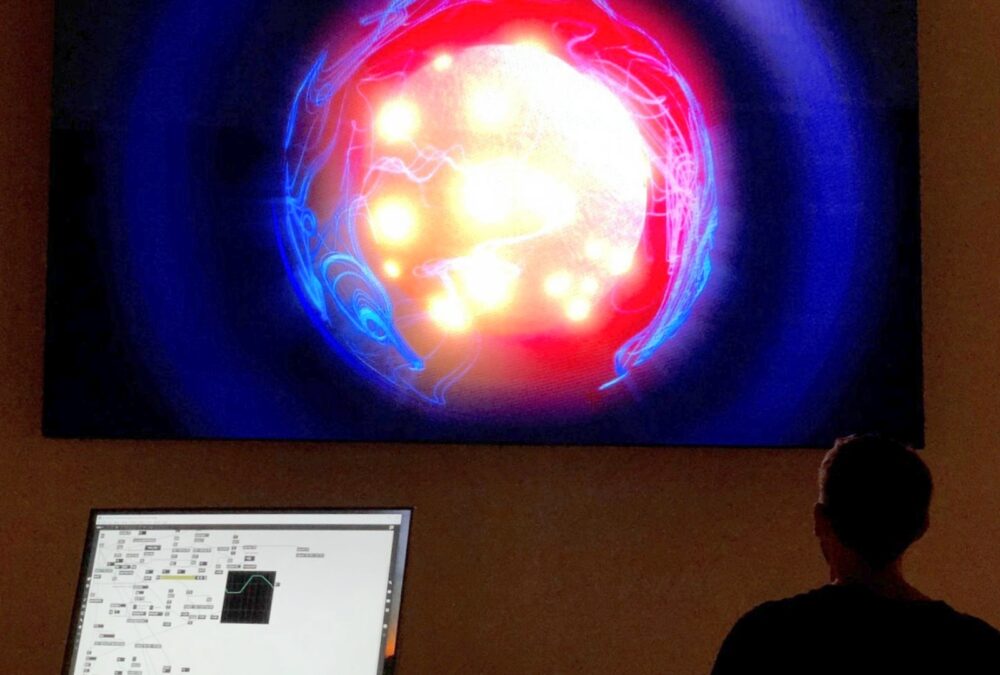

Multisensory room

The lab’s multisensory room is its main testing ground, embedded with projection screens and speakers to create immersive visual and audio simulations enhanced by tactile devices and other “toys” such as motion-tracking suits.

“The idea is to create complex, repeatable multisensory experiences and to experiment on connections between the senses,” says Wald.

He gives me a wearable to strap around my ribcage. As I breathe, my inhalations and exhalations display onscreen like a balloon inflating and deflating, accompanied by music.

Designed by HCI master’s student Oran Goral with visual artist Yoav Cohen, this simulation trains you to breathe more naturally and deeply. This can serve purposes such as helping patients control breathing during radiotherapy, which boosts treatment effectiveness.

Echolocating like bats

As my time in the BCT lab draws to a close, I begin wishing that some sensory-bending device could help me visualize all the brilliant ideas flying around the BCT lab.

Because we’ve only scratched the surface.

Wald speaks of future projects like creating novel senses to extend the human experience — and mapping those novel experiences in the brain.

“Maybe I can see through ultrasound, like bats. Maybe I can see infrared and heat,” he says. “Some animals have these abilities, and they give valuable insights on the world that humans don’t have.”

If anyone can do this, it’s Amir Amedi and his talented crew.

“In our lab we move between the very theoretical deep science to the very practical,” says Amedi. “The kinds of things we work on and the methodology we use make the lab unique in the neuroscience field.”

Abigail Klein Leichman is a writer and associate editor at ISRAEL21c. Prior to moving to Israel in 2007, she was a specialty writer and copy editor at a major daily newspaper in New Jersey and has freelanced for a variety of newspapers and periodicals since 1984.

First published on:Israel21c

The copyright belongs to Israel21c and the author.